https://elijahjm.wordpress.com/2018/01/10/turkey-has-its-eye-on-afrin-what-is-damascuss-position-difficult-challenges/

For more than six months, Turkey has been waving the flag of war over the Syrian-Kurdish city of Afrin (in the north-west) pouring in so far over 15,000 men and their equipment (artillery, logistics, medics, ammunition) these last few months. These preparations for war are apparently directed towards the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (Yekîneyên Parastina Gel – YPG), the Syrian branch of the PKK, Turkey’s fiercest enemy, of course. But what are positions of Russia and of the Damascus government towards the bellicose Turkish plans?

There is no doubt that Damascus is in an uncomfortable position regarding both the Kurds and the Turks. It is clear that the Syrian government sees in the Kurds a major threat due to the US’s support to the Syrian Kurdish militia (YPG) in the north-east of the country. These are used by the US forces to dislodge the “Islamic State” group (ISIS) and to achieve Washington’s interests and objectives in the Levant.

The Syrian President Bashar al-Assad also sees in Turkey yet another occupation force in the north of Syria, similar to the US forces: he would like to liberate the entire Syrian territory, contrary to Russia, which would prefer to end the war as quickly as possible and start negotiating around the table.

However, it must be said that the Turkish intervention in the north of Syria saved the country from what seemed an inevitable partition when the Kurds were heading from al-Hasaka towards Afrin to form a new Kurdish state along the Turkish-Syrian borders, supported, in addition, by the US. The Americans were looking for a large and stable military base (there are over 10 US temporary bases in al-Hasaka) in a non-hostile environment and among submissive populations and armed group, the YPG. In fact, the Turkish intervention was a necessity for Ankara itself and for its national security (categorically rejecting a Kurdish state on its borders that would fuel dangerously the eagerness of 16 million Kurds living in Turkey for an independent state). Therefore, Damascus’s and Ankara’s interests met in this same objective: to prevent a Kurdish enclave ruled by the US on Syrian territory.

But Damascus is aware that Ankara is not only aiming to stop a new Kurdish “state” on its border, it has a much larger appetite as regards Syria, and has had from the beginning of the war. When Turkey failed to see its ideological religious militants at the head of the government in Damascus, its eyes went towards Aleppo, the Syrian industrial city: this is where all the pro-Turkish Syrian militants were highly active at the end of the first year of war, dismantling giant plants to be smuggled and re-assembled in Turkey. In fact it was in 2012, a year after the beginning of the uprising, that pro-Turkish Syrian militants from rural Aleppo and Idlib had marched towards the industrial capital and dragged it into the war.

Certainly the inability of Damascus’s army to be engaged on multiple fronts simultaneously forced it to recover cities by order of priority and therefore it aimed for the most dangerous enemy in the first years of the war. Assad wanted to recover all main cities first, secure the capital, and to move onward towards Aleppo. When the Syrian Army and its allies liberated the Syrian industrial city of Aleppo, the Turkish dream fell apart, at least partially: the loss of Aleppo was compensated by the occupation of several other cities in the north of Syria still, to date, under Turkish direct control and influence.

However, Turkey did complain to the US regarding its intentions in Syria and its support to its Kurdish proxies, the enemies of Ankara. The US Defense Secretary James Mattis was very clear: US cooperation with the Kurds was not a question of choice but a necessity imposed by circumstances and the need to fight ISIS. It seems the Kurds were happy to be used by the US, and aware of being dropped later on. There is no doubt that the US won’t support the Kurds against its Turkish strategic alliance, particularly when Russia is so close and waiting to deprive Washington of its Turkish ally at the first false step.

Nevertheless, the Turkish presence and expansion in the north of Syria is deeply worrying to Damascus. Without Turkey, the US would no doubt seize a chunk of Syria. Yet with Turkey occupying Syrian territory (al-Bab, Jarablus, Azaz, Dabiq), Ankara is transforming the north into a Turkish enclave, imposing a governor, the Turkish language and a large military base.

For Damascus, the larger and most significant danger therefore comes more from the US than from Turkey. The Americans are allowing the Kurds to control 39,500 sq km (23% of the Syrian territory) and large reserves of oil and gas. Moreover, the US forces are offering protection to what remained of ISIS forces: they have allowed thousands of terrorists to leave via Turkey and to remain east of the Euphrates (the US is preventing the Syrian Army, its allies and Russia from crossing the river to eliminate ISIS), and therefore to represent a direct threat to Syria and its allies- especially when the time is coming to liberate the Syrian Golan Heights and attack the US’s first ally, Israel.

Assad has a dilemma, although his position is very clear: all Syrian territories must be liberated. The problem is, how to deal with two strong occupiers? Assad is certainly willing to resume fighting – especially now that he enjoys the upper hand and that the Syrian Army is growing very fast. Nevertheless, Russia is unwilling to continue the war, but is ready to eliminate al-Qaeda and its allies around Idlib since the city itself has been given to Turkey’s administration in Sochi following a de-escalation agreement. Assad also believes he has enough Syrian resistance forces, mirroring the Lebanese Hezbollah, who have sufficient training and readiness to start an insurgency against all occupation forces when the time comes.

According to Assad – and according to a close contact within his inner circle – Syria can free the north-east of Syria even if this takes many years. Assad observed the result of Hezbollah’s resistance in Lebanon following the 1982 Israeli invasion, and how, in the year 2000, Israel retreated unilaterally and unconditionally from most of the occupied territory in the south of Lebanon. Moreover, the Syrian President believes Ankara failed to overwhelm ISIS, and that only by common agreement was it possible to secure the militants’ withdrawal. According to Assad, the Syrian Armed forces (not only the regular Army) employ today thousands of Syrian nationals who have enough training (thanks to six years of war) to turn the north of Syria into hell on earth for both sets of occupying forces. And lastly, as long as the Kurds are hiding behind the US’s skirts, the Kurds of al-Hasaka will be considered traitors by Damascus.

Assad knows there are Kurds who support the Syrian government in Aleppo, Afrin and even al-Hasaka. The Syrian Army still maintains, along with its allies, a substantial force in the Kurdish province, not far from the US presence.

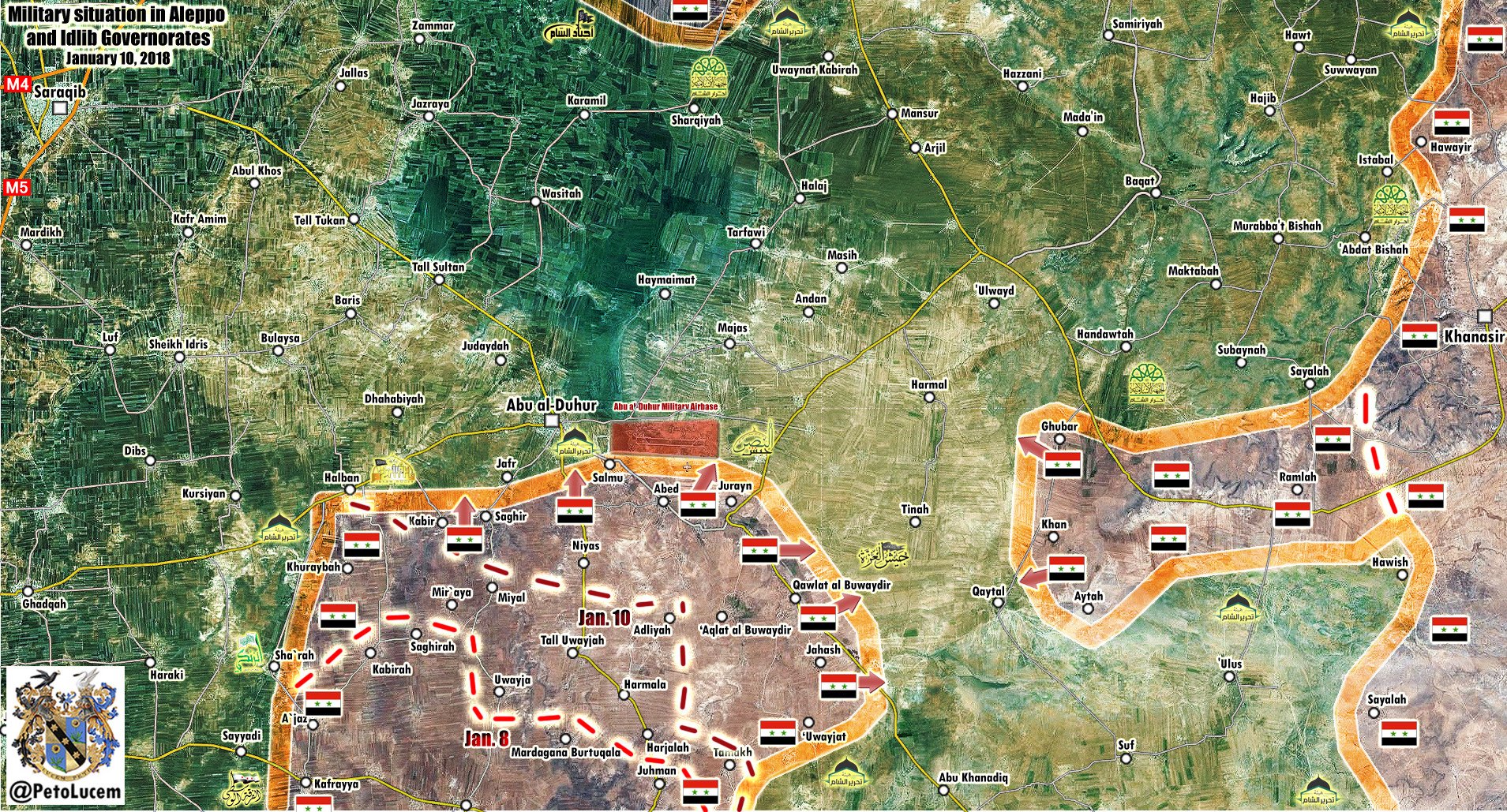

For now, Assad’s priority is to secure a large safety perimeter around Damascus and also around the principal Aleppo-Hama-Homs main road. The national Syrian resistance can manifest only when the country recovers, which will be slowly, and makes a start on rebuilding the devastating damage caused by the war, whose cost is estimated at over 300 billion dollars.

Assad can only call for both the Turkish and US forces to pull out, stating the official Syrian position. He can limit al-Qaeda to within Idlib, and cut the grass under its feet in the north of the country by allowing Turkey to try and control the city which, Damascus hopes, could eventually create an internal conflict between the jihadists themselves and the pro-Turkish Syrian groups. *(he means about Idlib)*

Russia is present in Afrin and is not expected to give a free hand to Turkey to occupy the city and withdraw from it. Russia doesn’t want further demographic shifts and is aiming to end the war, moving towards a political negotiation, including all parties. Russia doesn’t want to support forces in the south of Syria, nor beyond the Euphrates (under the US control) but is happy to clean up most of Idlib’s surrounding area.

The post-war – even with some fronts that are still active – can be expected to be much more difficult than the war itself. Many interests intertwine, and two strong countries – Turkey and Iran – have forces in Syria, as well as two superpower countries (Russia and the US), and will require navigating between these, taking into consideration the interests of the “axis of the resistance”- plus Israeli nervousness. Diving into peace negotiations, uniting rebel groups that were split for all the years of war, reconstructing the damaged country and its infrastructure, and achieving reconciliation among Syrians are all near impossible tasks for any Syrian government to face this year 2018.

kvs

kvs