Japan Faces Challenging Choices for Cash-Strapped Air Force

Critics have raised concerns that Japan’s Air Self-Defense Force (ASDF) could find itself with only a modest number of fifth-generation aircraft backed by obsolescing fourth-generation planes, based around the F-2 and F-15s, that lack interoperability.

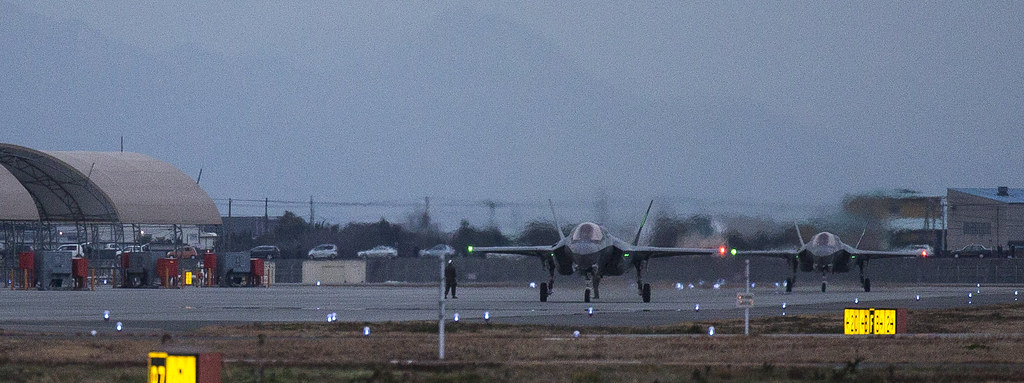

For example, at present funding levels, the ASDF can only procure 42 F-35s at a rate of a handful a year, meanwhile diverting scarce resources to update its legacy fleet. This year, the ASDF can only afford to buy six F-35s while upgrading 11 F-2s with modern digital communications systems.

The recent ballyhooed unveiling of the putative fifth-generation X-2 Shinshin stealth fighter demonstrator and the future availability of the short takeoff/vertical landing F-35B on Japan’s carrier-convertible DDH Izumo-class helicopter carrier seem to offer the ASDF some pathways to building a more effective force. But do they?

Richard Aboulafia, vice president, analysis, at the Teal Group suggested that given budget constraints, costs and the dead-end nature of the costly F-2 program, ASDF’s most likely scenario will be some additional F-35s and more F-15 upgrades. Japan might even consider buying more up-to-date F-15s, but given the funding priority of the first 42 F-35s, cash for more F-15s is unlikely to be provided, he said.

“One thing's certain: The F-15 fleet will be the most important JASDF component for decades to come. In terms of range and payload the F-15s are hugely important, and upgrading them will be a very high priority. They're synergistic with the F-35s. Upgrading the F-2 fleet is somewhat tertiary in terms of priorities,” Aboulafia said.

“Japan has made a significant investment in F-35, as they should have. But they can’t afford to have substantially more F-35s delivered any sooner … and … the F-2s are important only in keeping the Japanese defense industrial base relatively proficient in basic design and manufacturing,” said Steven Ganyard, president, Avascent International.

Ganyard also suggested an F-15 upgrade strategy was the most logical scenario, since the ASDF’s F-15s have substantial life left but desperately need to be upgraded.

“The threat to Japan is not Chinese fighters. It’s thousands of cruise and ballistic missiles that could easily cut off all Japan south of Kyushu. This most important reason to have both F-35s and upgraded F-15s with AESA radars is the cruise missile threat of low flying, low [radar cross section] missile salvos that could quickly become overwhelming. This also points out the importance of a 'raid breaker' capability along the Nansei Shoto, perhaps mobile rail guns,” Ganyard said.

In this light, a joint upgrade program between Japan and the US would share development costs, reduce risk and increase interoperability. The result would be the kind of air force that the US, Israel, Australia and Singapore will have, a mix of aircraft and integrated operations with both fifth-generation and 4+ generation fighters, Ganyard said.

The deeper problem, analysts agree, is that Japan needs to pull back from funding aircraft that are not internationally competitive, such as the F-2, the C-2 and the P-1, and refocus its strategy and R&D resources on a few world class products and buy what it isn't able to build.

This makes the Shinshin look increasingly like a redundant bauble, analysts said.

“Could Shinshin be developed as a poor man’s stealth fighter that, say, Europe and/or the US might be interested in co-developing and India, Australia, et al might be interested in buying? That would certainly cut unit costs. I have no idea what the upside for Shinshin is, though,” said Jun Okumura, visiting scholar at the Meiji Institute for Global Affairs, and a former official of the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, which supports domestic weapons platform development.

Spending on Shinshin would take billions of dollars away from force enhancement and replacement and put it toward development of an unknown airframe, said Aboulafia.

“It would represent the triumph of national technology development and prestige over actual military needs, unless they had some kind of higher goal, such as an export-oriented plane,” he said.

“Japan should not develop a poor man’s anything. It wastes money and only makes the country more vulnerable,” Ganyard said.

Speculation bubbled up a few years back that Japan might consider acquiring the F-35B when it was revealed, for example, that the DDH Izumo-class helicopter destroyers come equipped with F-35B compatible elevators.

“The F35B is a luxury item that I can’t see the ASDF going for. Aircraft carriers are slow and vulnerable and need lots of support. So, unless you really want to project your naval power to the South China Sea and beyond, or the Japan-US alliance breaks down, I would forget about it," Okumura said.

Aboulafia agreed, saying that fixed-wing carrier aviation sounds appealing from a force projection and regional presence standpoint, but that it was basically unaffordable for Japan.

“As it is, the ratio of resources to intentions is way too high; standing up a carrier strike force would make the problem much worse. If Japan adds billions of dollars to the defense budget that's one thing … those 17 V-22s are barely affordable as it is,” Aboulafia said.

But Ganyard said one reason there has been a shift in thinking away from the F-35B is the opportunity that the US Navy’s Ford-class carrier presents with electro-magnetic aircraft launch systems (EMALS).

“Without much challenge Japan’s current DDH could be fitted with EMALS and its associated arresting gear. Add an angled deck, a bit more length and displacement, and the JMSDF is back in the fixed-wing aviation business," Ganyard said.

“While it might take some very senior level direction to carry out such a radical shift, of all the countries in the world, Japan would strategically benefit the most from a return to carrier aviation,” Ganyard said.

Critics have raised concerns that Japan’s Air Self-Defense Force (ASDF) could find itself with only a modest number of fifth-generation aircraft backed by obsolescing fourth-generation planes, based around the F-2 and F-15s, that lack interoperability.

For example, at present funding levels, the ASDF can only procure 42 F-35s at a rate of a handful a year, meanwhile diverting scarce resources to update its legacy fleet. This year, the ASDF can only afford to buy six F-35s while upgrading 11 F-2s with modern digital communications systems.

The recent ballyhooed unveiling of the putative fifth-generation X-2 Shinshin stealth fighter demonstrator and the future availability of the short takeoff/vertical landing F-35B on Japan’s carrier-convertible DDH Izumo-class helicopter carrier seem to offer the ASDF some pathways to building a more effective force. But do they?

Richard Aboulafia, vice president, analysis, at the Teal Group suggested that given budget constraints, costs and the dead-end nature of the costly F-2 program, ASDF’s most likely scenario will be some additional F-35s and more F-15 upgrades. Japan might even consider buying more up-to-date F-15s, but given the funding priority of the first 42 F-35s, cash for more F-15s is unlikely to be provided, he said.

“One thing's certain: The F-15 fleet will be the most important JASDF component for decades to come. In terms of range and payload the F-15s are hugely important, and upgrading them will be a very high priority. They're synergistic with the F-35s. Upgrading the F-2 fleet is somewhat tertiary in terms of priorities,” Aboulafia said.

“Japan has made a significant investment in F-35, as they should have. But they can’t afford to have substantially more F-35s delivered any sooner … and … the F-2s are important only in keeping the Japanese defense industrial base relatively proficient in basic design and manufacturing,” said Steven Ganyard, president, Avascent International.

Ganyard also suggested an F-15 upgrade strategy was the most logical scenario, since the ASDF’s F-15s have substantial life left but desperately need to be upgraded.

“The threat to Japan is not Chinese fighters. It’s thousands of cruise and ballistic missiles that could easily cut off all Japan south of Kyushu. This most important reason to have both F-35s and upgraded F-15s with AESA radars is the cruise missile threat of low flying, low [radar cross section] missile salvos that could quickly become overwhelming. This also points out the importance of a 'raid breaker' capability along the Nansei Shoto, perhaps mobile rail guns,” Ganyard said.

In this light, a joint upgrade program between Japan and the US would share development costs, reduce risk and increase interoperability. The result would be the kind of air force that the US, Israel, Australia and Singapore will have, a mix of aircraft and integrated operations with both fifth-generation and 4+ generation fighters, Ganyard said.

The deeper problem, analysts agree, is that Japan needs to pull back from funding aircraft that are not internationally competitive, such as the F-2, the C-2 and the P-1, and refocus its strategy and R&D resources on a few world class products and buy what it isn't able to build.

This makes the Shinshin look increasingly like a redundant bauble, analysts said.

“Could Shinshin be developed as a poor man’s stealth fighter that, say, Europe and/or the US might be interested in co-developing and India, Australia, et al might be interested in buying? That would certainly cut unit costs. I have no idea what the upside for Shinshin is, though,” said Jun Okumura, visiting scholar at the Meiji Institute for Global Affairs, and a former official of the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, which supports domestic weapons platform development.

Spending on Shinshin would take billions of dollars away from force enhancement and replacement and put it toward development of an unknown airframe, said Aboulafia.

“It would represent the triumph of national technology development and prestige over actual military needs, unless they had some kind of higher goal, such as an export-oriented plane,” he said.

“Japan should not develop a poor man’s anything. It wastes money and only makes the country more vulnerable,” Ganyard said.

Speculation bubbled up a few years back that Japan might consider acquiring the F-35B when it was revealed, for example, that the DDH Izumo-class helicopter destroyers come equipped with F-35B compatible elevators.

“The F35B is a luxury item that I can’t see the ASDF going for. Aircraft carriers are slow and vulnerable and need lots of support. So, unless you really want to project your naval power to the South China Sea and beyond, or the Japan-US alliance breaks down, I would forget about it," Okumura said.

Aboulafia agreed, saying that fixed-wing carrier aviation sounds appealing from a force projection and regional presence standpoint, but that it was basically unaffordable for Japan.

“As it is, the ratio of resources to intentions is way too high; standing up a carrier strike force would make the problem much worse. If Japan adds billions of dollars to the defense budget that's one thing … those 17 V-22s are barely affordable as it is,” Aboulafia said.

But Ganyard said one reason there has been a shift in thinking away from the F-35B is the opportunity that the US Navy’s Ford-class carrier presents with electro-magnetic aircraft launch systems (EMALS).

“Without much challenge Japan’s current DDH could be fitted with EMALS and its associated arresting gear. Add an angled deck, a bit more length and displacement, and the JMSDF is back in the fixed-wing aviation business," Ganyard said.

“While it might take some very senior level direction to carry out such a radical shift, of all the countries in the world, Japan would strategically benefit the most from a return to carrier aviation,” Ganyard said.

Rodion_Romanovic

Rodion_Romanovic