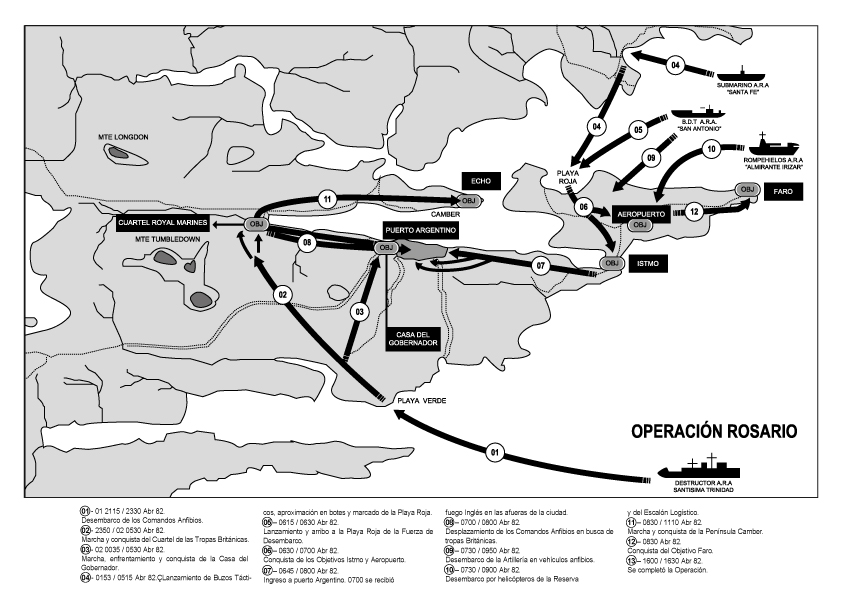

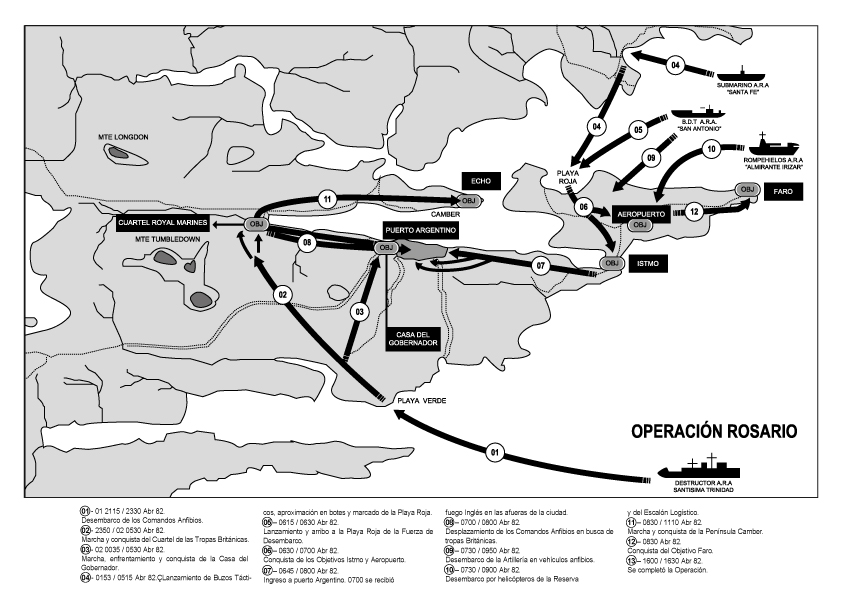

Operation Rosario.

aircraft carrier ARA “25 de Mayo”

On March 28, the Amphibious Task Force 40 (FT 40) under the command of Rear Admiral Walter Oscar Allara set sail from the Puerto Belgrano Naval Base.

Operation Rosario began, for the recovery of our Malvinas Islands.Malvinas, D-Day: Operation Rosario, a furious storm and the adrenaline of the landing on April 2, 1982

That day, 40 years ago, Argentine troops set foot in the Malvinas, but the preparations and the war of nerves had begun long before, in the utmost secrecy. One of those protagonists was Roberto Reyes, then a young second lieutenant, who felt that he did not deserve everything that was happening to him. Day by day of a military operation that had been months in the making

Adrian Pignatelli

By

Adrian Pignatelli

It happened on Friday, March 26, 1982. The officers of the 25th Infantry Regiment listened intently to Lieutenant Colonel Mohamed Alí Seineldín, who was accompanied by the head of the engineering company. In the midst of a reverential silence they attended to the orders and instructions that he was giving them in the situation room, with the sand table where the actions were planned. They were being informed that the recovery operation for the Malvinas Islands had been launched. One of those young officers was Second Lieutenant Roberto Reyes. He was 24 years old and felt that he received more than he deserved.

A few days before, on February 1, 1982, Seineldín had learned that the 25th Regiment, which he was in command, would be the only Army unit that would make up the landing force. He had to execute the action plan.

The incident that began on March 19 in Port Leith, on the Georgia Islands, when workers from an Argentine company went to dismantle a whaling factory, precipitated the events. On the 23rd, the Navy, which had been working on the project since the previous year, had already been asked about the earliest date to carry out the operation.

On the afternoon of the 25th, the Military Junta had ordered that the fleet should depart on the 28th at noon and that on April 1 they would disembark on the islands. Between the 26th and the 28th the ships that would participate were duly supplied.

Company C of the 25th Regiment, led by First Lieutenant Carlos Esteban, would participate in the landing force. It was made up of the “Bote” sections under the command of Lieutenant Roberto Estevez and “Romeo” under Second Lieutenant Juan José Gómez Centurión, which would lead an amphibious operation to control and occupy Darwin. A third section, called “Gato,” under the command of Second Lieutenant Roberto Reyes, would be responsible for an airmobile operation to capture the governor.

destroyer ARA “Santísima Trinidad”

While Seineldín was giving his orders, that March 26, Gómez Centurión secretly removed the cast from his hand that he had been wearing for days due to an accident he had suffered. He didn't want to be left out of the historic day for anything in the world.

They had to prepare his equipment quickly, since in a few more hours they would leave. Seineldín gave them an order that some even took with annoyance: they had to carry their saber because they were going to go to battle.

On Saturday, March 27, they went by plane to the Comandante Espora air-naval base and the next day, at sunrise, they boarded the fleet.

Sunday the 28th was a radiant day. At night the Cabo San Antonio, a tank transport ship, began to rock. She had set sail that day from Puerto Belgrano carrying part of the landing force.

landing ship “Cabo San Antonio”

On the 29th, the 30th and the 31st they endured a southwesterly storm that the embarked infantry troops had never even dreamed of having to face.

The operation had to be “bloodless, surprising and short-lived.” The landing force was made up of Cape San Antonio; the transport ship Islands of the States; the Almirante Irízar Icebreaker; the Santa Fe Submarine; the frigates Santísima Trinidad and Hércules and the corvettes Drummond and Granville. Further away, the 25 de Mayo aircraft carrier, its Aeronaval Group and the continent's air force bases.

ARA corvette “Guerrico”

Those from Reyes would be the only Army troops to participate in the actions in Puerto Argentino that Friday, April 2. He was to assemble with the soldiers incorporated two months earlier a light faction with good firepower and rapid deployment. Everyone understood that they were part of something important. They couldn't believe what they were experiencing.

In the five-story dormitories with bunks of the San Antonio, the 37 troops of the 25th Regiment were accommodated in the small space separated by narrow corridors and poor ventilation. The first task they addressed was improving the stowage of materials.

The ship, a mass 144 meters long, moved a lot in the choppy sea. The dizziness and discomfort of those who were used to moving with their feet on the ground immediately took their toll. What they still did not know is that the wobbles would last until the day of disembarkation.

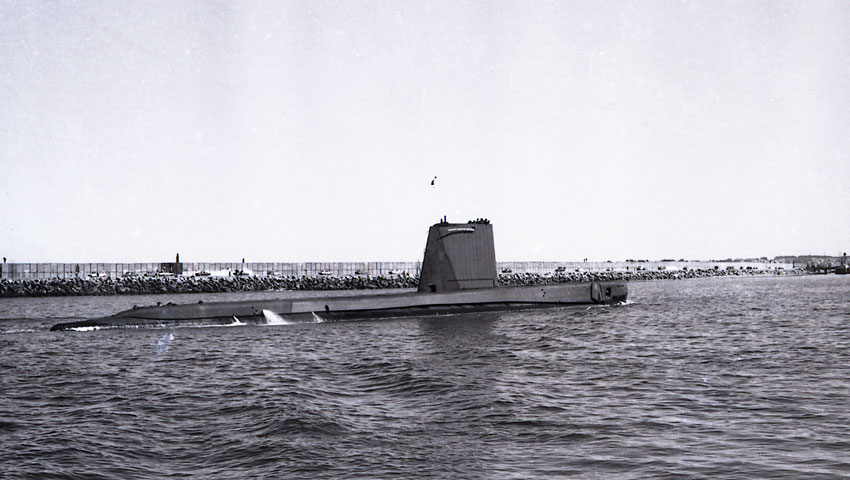

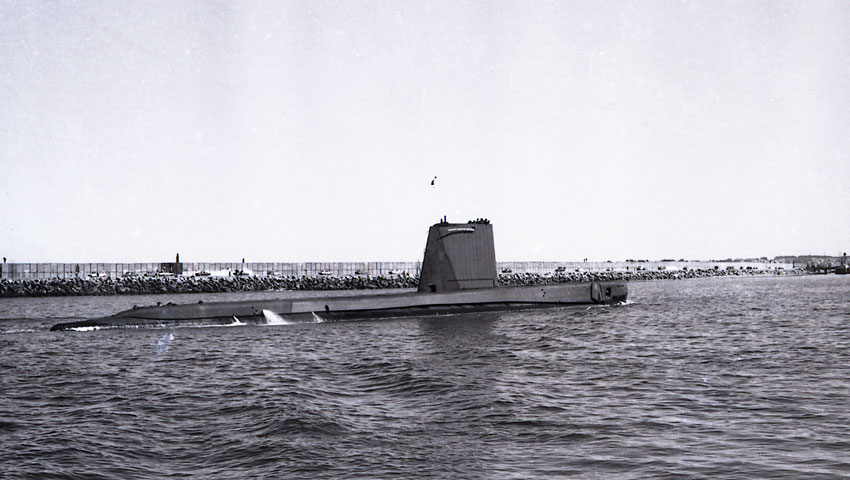

ARA submarine “Santa Fe”

The officers tried to keep their men busy. Defense practices against fire and abandonment of the ship were carried out on the upper decks. The soldiers did not know where they were going. They speculated about a conflict with Chile or that they were going to the aid of a Central American country. They were sailing south and, upon reaching Río Gallegos, they would head towards the islands.

If the first day the sea was rough, on the second the conditions worsened to such a point that the violent inclinations of the ship to port and starboard alternately lifted the soldiers from the ground and threw them against the walls. Those who could did some physical exercises and others cleaned the weapons. They prayed to reach their destination as quickly as possible. Few paid attention to the three shifts to eat. There were people who didn't eat anything those five days.

Fearing that the storm would cause the operation to be suspended, Lieutenant Colonel Seineldín proposed to Admiral Carlos Büsser, commander of the landing force, to change the name of the operation, baptized "Blue." Seineldín recalled that in 1806, during the first English invasion, the forces that Santiago de Liniers had gathered in Colonia and had embarked with the bow to Buenos Aires, had been left at the mercy of a southeasterly force. Liniers put his forces to protect the Virgin of the Rosary. They were able to reach port safely while the English ships that tried to prevent them suffered serious damage.

From then on, the operation was renamed Rosario.

On the third day of navigation, the leaders of the factions that would disembark were summoned to carry out rehearsals for the actions they would deploy on D-Day. Second Lieutenant Reyes received cartography and other details to adjust the raid they had to carry out on the governor's house. The young officer had to explain how he would carry out this operation and the corresponding adjustments were made.

The LVTP 7 amphibious vehicles used in the landing, in the Cabo San Antonio warehouse.

He was all ready for the planned landing on April 1.

On the fourth day, Büsser decided to postpone the landing until the next day. The English had detected the Argentine forces and were preparing the defense, fortifying areas of interest. The tactical surprise had been lost.

The missions were changed. The western area of Yorke Bay would be used as a landing site; tactical divers who came on the submarine Santa Fe had to mark the landing beach; The order to seize public services, at that point reinforced by the British, was cancelled; It was decided that the Seineldín troops would take control of the airport runway and not the Air Force personnel, as planned; the tactical and amphibious commands would head to the governor's house; another group of commandos were to take over the Moody Brook barracks.

The helicopter that was supposed to transport Reyes and his section had been damaged due to navigation. So, instead of taking the house of Governor Rex Hunt, it was determined that they should take over the airport, eliminating the English resistance and clearing the runway, strewn with vehicles and machinery left by the Royal Marines and they had also turned off the San Felipe lighthouse. The amphibious commandos would man the governor's residence.

Reyes and his men then had to familiarize themselves with boarding and disembarking practices of the tracked amphibious vehicle (CAV) with which they would travel to the beach. VAO 10 had capacity for 26 members of the section; The remaining 11 would support the landing from the San Antonio. The adrenaline made them forget about the dizziness.

At 6 p.m. on April 1, after hearing mass over a loudspeaker, it was the commander of the landing force who revealed the objective of the mission. At the Holy Trinity the same message was read at the same time. There was excitement, joy, shouts of joy and cheers for the country. That night the sea had calmed down, but no one slept.

At dawn on the 2nd, the movements through the narrow corridors of the lower decks were incessant. The hold of the ship was filled with the smell of the running engines of the amphibious vehicles. The orders and shouts mixed with the scream of the radios searching for frequencies. The lights remained off.

Reyes ordered his men to put on their life jackets. When Sergeant Colque finished distributing them, his look said it all: there was none for him or Reyes. They prayed they wouldn't have to need them.

Map of Operation Rosario

At 5:30 Reyes and his men were ready. This is what they told Seineldín, who harangued them. His words were interrupted by the order that came from the hold's speakers: time to board.

Radio silence had been ordered inside the amphibious vehicles; The side and upper doors were closed and the soldiers were able to guess the faces of their companions thanks to a faint red interior light. In silence they waited for the order to “first wave into the water.”

Between 6:05 and 6:10 the bow hatches opened, the noise of the engines seemed to attenuate and the smoke from the 21 vehicles dissipated due to the change in air. Minutes later the men felt the vehicle taxi and suddenly found themselves floating. Seineldín had ordered the soldier Juan Pessaresi to record Cala Cuerda, a rifle march executed by the patriots during the English invasions.

:quality(85)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/infobae/T7CY32PXKZE7LCV6TP7EMBHEJA.jpg)

Captured British flag.

The amphibious vehicles headed toward “Playa Rojo W”, the point where they would disembark. That place had been secured hours before by tactical divers taken by the Santa Fe submarine.

They realized that they were not receiving fire, although in the distance they could hear shots in the direction of the city. Reyes had ordered the deck covers to be removed from the vehicle and, in the middle of an incredibly calm sea, illuminated by the sparkles of dawn, he saw the lights of Puerto Argentino. He looked back at the landing fleet.

The cries of joy returned when they felt that the caterpillars had touched the rocks and were moving across the sand. They were in Malvinas.

Troops from the Marine Infantry Battalion No. 2 and Reyes and his section headed to the airport. They found it empty and the Royal Marines had not even left booby traps. They dedicated themselves to removing around thirty machines and trucks that were obstructing the runway.

Then, he received the order to rake one of the streets of Puerto Argentino, in the direction of the governor's house. They had to capture the English soldiers they found, and take special care not to cause casualties in the population. They only found two British paramedics who were heading to the hospital to treat the first wounded.

:quality(85)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/infobae/CKGXW6URCFD3FFBMZD4QN7VA2E.jpg)

The amphibious vehicle 10 in which the Reyes section disembarked. In the foreground you can see Seineldín and behind, in a beret, Second Lieutenant Reyes.

The Argentines had their first casualty, Lieutenant Commander Pedro Giacchino, when a shootout broke out with marines entrenched in the governor's house. In that action, frigate lieutenant Diego García Quiroga and first corporal Ernesto Urbina were wounded.

While the commander of the landing force was meeting with the governor at his residence and in the garden the Royal Marines were guarded by amphibious commandos, the Hercules landed, transporting the rest of the 25th Regiment. And troops arrived at the airport transported by helicopter from the Irízar.

Around noon, a formation was held in the patio of the house to officially materialize the recovery of the islands. During the preparations the halyard was cut from the mast, and Second Lieutenant Reyes climbed to the top to hook it. Some interpreted it as a bad omen.

“Good morning, Argentines,” de facto president Leopoldo Galtieri greeted his cabinet at 7:30. The new governor, General Mario Benjamín Menéndez, was present. Minutes before 10 in the morning, the Military Junta issued the first statement: “The Armed Forces, in a joint action, in order to recover for the national heritage the territories of the Malvinas, Georgias and South Sandwich Islands, "They are engaged in combat to achieve the stated objective."

People gathered in the Plaza de Mayo and after 2:30 in the afternoon, Galtieri looked out on the balcony. "We will accept dialogue after this forceful action, but with the conviction that dignity and national pride must be maintained at all costs and at any price." Then he went out into the square and mingled with the people.

Puerto Stanley quickly changed to Puerto Rivero, in honor of Gaucho Rivero, and as of April 16, the capital was officially named Puerto Argentino.

Seineldín, the same one who had ordered his officers to carry their sabers, a symbol of command, and the one who proposed changing the name of the operation, went to the head of the airport runway and with a formation watching him, dug a hole and buried a rosary beads. They were in Malvinas. The war had begun.

https://www.infobae.com/sociedad/2022/04/01/malvinas-dia-d-la-operacion-rosario-una-furiosa-tormenta-y-la-adrenalina-del-desembarco-del-2-de-abril-de-1982/

:quality(85)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/infobae/OBSOMO6BYFHYJPOQLAAC2WMICE.jpeg)

Raising of the flag in Puerto Argentino.

:quality(85)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/infobae/T7CY32PXKZE7LCV6TP7EMBHEJA.jpg)

:quality(85)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/infobae/CKGXW6URCFD3FFBMZD4QN7VA2E.jpg)

:quality(85)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/infobae/OBSOMO6BYFHYJPOQLAAC2WMICE.jpeg)