Russian Defense Spending: any Room for Savings?Konstantin Makienko

Moscow Defence Brief May 2012

During his presidential election campaign Prime Minister Vladimir Putin repeatedly vowed to stick to all the previously announced — and very expensive — defense spending plans. The rearmament program for the Russian Armed Forces alone, i.e. not counting other uniformed agencies, will cost an estimated 19.5 trillion roubles (500 billion euros) over the next decade. In other words, Russia will spend an average of 50 billion euros a year on new weapons for the next 10 years. The corresponding figure in France, which has a slightly larger economy, is only 15bn euros. The MoD also intends to keep ramping up spending on such items as housing and catering, payroll, education and combat training.

Many specialists are voicing concerns that Russia is becoming too militarized, and that such ambitious defense spending is too burdensome for the fragile Russian economy; former finance minister Aleksey Kudrin was probably the most vocal critic. Under the existing plans Russia should spend a relatively manageable 2.9 per cent of its GDP on defense. There is a danger, however, that the actual figure could reach 4 per cent, which would be a real problem. Projections by the Ministry of Economic Development suggest that the government’s defense spending plans require the Russian economy to keep growing by at least 4 per cent every year. But it is far from certain that Russia’s corrupt and paternalistic economic system, which is based on state-owned monopolies, can actually sustain such growth, modest though it may seem by the standards of other developing markets. The Russian economy’s performance in 2011 suggests that even such sluggish growth is predicated on the oil prices remaining at anomalously high levels of above 100 dollars a barrel. That is why the main risk facing the State Armament Program 2020 is macroeconomic instability and unpredictability. It will take a relatively small reduction in the oil and gas prices (which is not at all unlikely) to make Putin’s pre-election promises, including his defense spending pledges, unrealistic. No wonder then that the Finance Ministry is rumored to be studying various options for spending cuts. Some reports claim that spending on national defense could be slashed by 0.5 per cent of GDP.

The question is, can savings be made without jeopardizing the ongoing reform of the Russian armed forces? We believe that the answer is yes.

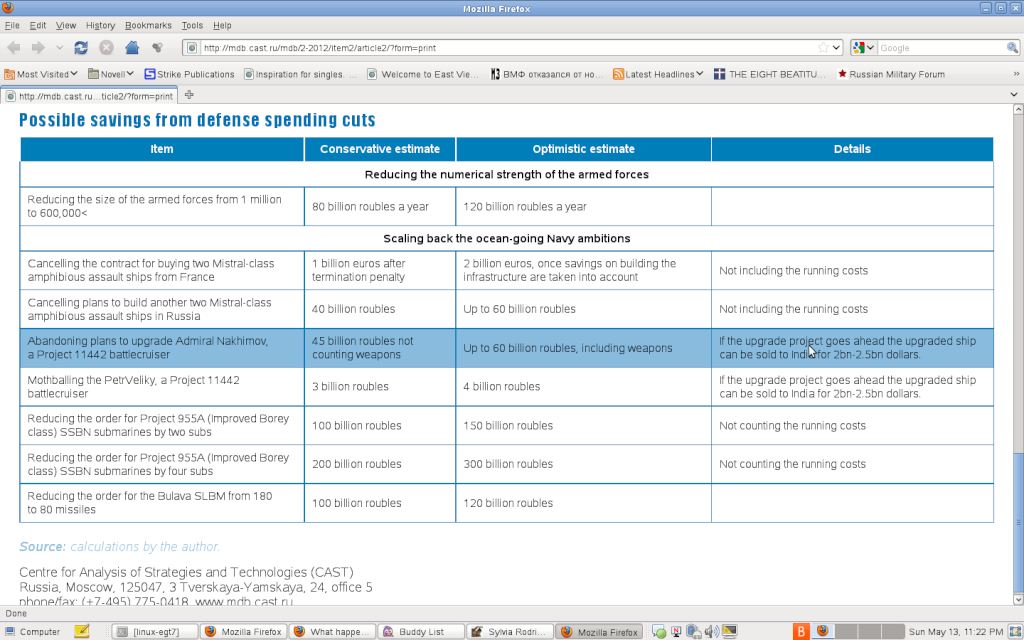

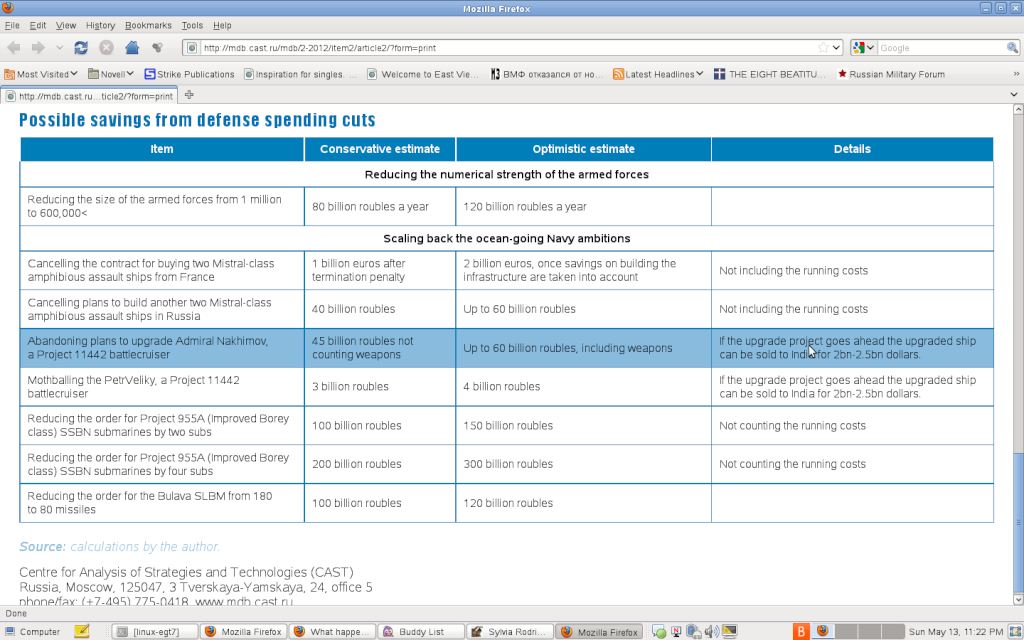

If and when the time comes for such measures, the biggest savings can be made by reducing the numerical strength of the armed forces and by shelving several costly, lengthy and technically risky projects in the naval weapons segment.

As present the size of the Russian army has been set at 1 million people. But the country is entering a demographic trough; new conscripts will have to be recruited from among the generation born during the severe economic and political crisis in the early 1990s. A very large chunk of this demographic group is simply unfit to serve for health reasons; besides, military service is universally loathed by young people. Even if the Russian armed forces can find enough conscripts to stay at the 1 million mark, a very large proportion of those conscripts will be substandard material. That is why it would be entirely logical to cut the Russian army to 850,000 or even 800,000 people. Under the most radical scenario — and if the situation in the North Caucasus and Central Asia permits — Russia could well risk even deeper cuts, all the way to 650,000-700,000 people. But in that case the Russian military planners would have to accept that at any one time the country will be able to handle only a single local armed conflict not much larger in scale than the August 2008 war with Georgia. In the event of a real threat of two simultaneous conflicts (i.e. in the Caucasus and in Central Asia at the same time), Russia would need to have a minimum of 850,000 people under arms.

Another area where large savings can be made is the Navy. More precisely, Russia may have to relinquish some elements of its ocean-going fleet. These are very expensive and require only the best human resources, which are already in short supply. The hard truth is that Russia can afford to demonstrate power, but not to project it. Besides, all of its vital national interests and all the main military threats (with the exception of Japan’s territorial claims to the Kuril Islands) are on the continental land mass. They do not require Russia to maintain its naval strength, let alone ramp it up. That strength is prestigious but far too expensive. As for the Kuril Islands, even if Russia were to press ahead with its current plans it would not be able to achieve the same numbers, and certainly not the same capability, as the Japanese air force and especially the Japanese navy — not any time soon, anyway. If Tokyo chooses the Falklands scenario, a nuclear escalation will be all but inevitable.

In practice relinquishing the ocean-going ambitions would translate, first and foremost, into cancelling the pointless and quite possibly corruption-driven contract with France for two Mistral-class amphibious assault ships, even though Russia would have to pay a termination penalty. By walking away from the deal to buy the first two of these ships Russia will save 1.2bn euros minus the penalty (about 10-15 per cent of the value of the contract). Another two of these ships are supposed to be built at Russia’s own shipyards, which will probably increase their price tag by 10-15 per cent. By cancelling that part of the plan the MoD can save another 1.5bn euros or so. In addition, an estimated 40bn roubles (1bn euros) can be saved by not building the infrastructure required by the Mistral-class ships. Finally, the running costs of the Mistral are hard to estimate at this moment, but they will clearly be huge because the Russian Navy will depend entirely on the French suppliers. This is the final area of Mistral-related savings.

As part of the same strategy to reduce its global power demonstration capability Russia should abandon its current plans to repair and upgrade Admiral Nakhimov, a Project 11442 heavy nuclear-powered guide missile battlecruiser, let alone the two older ships of the same class, Admiral Ushakovand AdmiralLazarev. The cost of the Admiral Nakhimov upgrade project is now estimated at 45bn roubles (more than 1bn euros), and it will inevitably continue to grow. The two older cruisers will be even more expensive to renovate. The MoD would also do well to abandon the plan for medium-grade repairs of the PetrVeliky, a Project 11442 heavy nuclear-powered guide missile battlecruiser. The ship is an impressive status symbol, but the single task it was built for is to take on aircraft carriers. For practical purposes Russia has very little use for it. The most sensible solution would to mothball the PetrVeliky after 2016, when the time comes for its scheduled repairs. At some point in the future, when the economic situation permits, both of the existing Project 1144 Orlan ships (and possibly the hulls of another two) can be used as versatile assault platforms or as specialized air defense and missile defense ships. Finally, as part of the same savings strategy Russia should decommission all of its remaining Project 956 (Sovremennyi class) destroyers; the ships are very expensive to run and their power plants are not very reliable. The approach we are proposing is based on forming a new general-purpose core of the Russian Navy from 12-15 newly bought Project 22350 (Admiral flotaSovetskogoSoyuzaGorshkov class) frigates and Project 11356R (11357, Admiral Grigorovich class) frigates.

As for the naval component of the nuclear triad, it is very expensive to run; in fact, it is much more costly and probably less resilient than the ground-based Strategic Missile Troops. But the naval component has been at the center of the Russian strategy to augment its nuclear deterrence capability for the past 15 years. It is too late to reverse that strategy. Nevertheless, if the Russian economy takes a turn for the worse it might make sense to reduce the number of the Project 955 Borei strategic nuclear missile submarines Russia plans to build from eight to six.

Building a modern navy is an extremely expensive and time-consuming business. In addition, once the ships have been built they require highly trained people to run them, and those are in short supply. Thanks to Russia’s geographic situation, the Navy has always played a secondary role in its military capability. To be completely honest, it would not be an utter disaster if Russia were to limit its naval strength to nuclear missile submarines stationed in the North and on Kamchatka, plus some naval forces to bolster the combat resilience of those subs. Russia is the world’s firth or sixth largest economy; over the coming decade it will probably slip further down the global ranking. Its ambition of global power projection — or even power demonstration — is becoming increasingly unaffordable. Russia’s prestige would suffer if it were to abandon those expensive ambitions. But perhaps getting rid of its great-power delusions would actually be the first step towards reversing the country’s stagnation and marginalization.