Moscow Defence Brief

Aleksandr Privalov

The Russian army’s military automotive fleet remains a key instrument of troop mobility and an important factor in their combat readiness. Maintaining and improving that fleet should therefore be high on the MoD’s agenda.

Terms and definitions

The term “military automotive fleet” (MAF) covers vehicles built to the Russian MoD’s specifications; its uses include serving as platforms and towing vehicles for weapons systems; combat support; and transportation of personnel and cargos. In Russia, MAF vehicles are supplied under the Russian government’s Defense Procurement Program.

Based on the above definition, vehicles imported from non-CIS countries are not, strictly speaking, part of the Russian MAF. That is why models such as Iveco LMV, MAN FX77, Mercedes-Benz Zetros, Volvo FMX, and other actual or potential imports, which have attracted a lot of media coverage in recent years, are not covered in this article.

The Russian MAF includes the following categories of vehicles:

Multi-Purpose Vehicles (MPV) – off-road and all-terrain vehicles designed to carry military personnel and cargo, as well as to serve as towing trucks or platforms for weapons systems

Special Wheeled Chassis and Towing Vehicles (SWCTV) – wheeled all-terrain vehicles designed to serve as weapons platforms, weapons towing vehicles, or combat support vehicles

Military Tracked Vehicles (MTV) – self-propelled tracked vehicles designed for various military uses (towing vehicles; tower-transporters; solitary or articulated all-terrain transporters; and special tracked chassis)

Tractors

Road trains and trailers

Vans and containers

Maintenance, repair and evacuation vehicles

Over the past 10 years two more categories have emerged:

Tactical Vehicles (TV) – special protected off-road vehicles designed as weapons platforms or towing trucks, as well as personnel transporters

Heavy transporters – dual-use all-wheel drive vehicles which share parts and components with civilian models; these are used as weapons platforms and weapons transporters, as well as general-purpose military transports.

MAF vehicles also fall into different categories depending on the type of chassis (wheeled or tracked); engine (petrol, diesel, gas, electric, and others, including multi-fuel engines); cargo capacity; protection class; etc. Another thing to note is that the Soviet armed forces used several other terms; this article mentions a few of them, including “general-purpose vehicles” or “general military vehicles”; these include various types of transports.

This article does not cover tractors, road trains and trailers, vans and containers, or maintenance, repair and evacuation vehicles. It also covers only select MTV vehicles because of the abundance of various suppliers and models in this category.

The term “dual-purpose hardware”, which emerged in the 1990s, covers vehicles designed to comply with the MoD’s specifications but meant for civilian as well as military applications. All of the MAF categories can be dual-purpose vehicles, but the models meant for civilian use are supplied without any military or special-purpose hardware (weapons mounting components, thermal imagers, air filters, etc.).

Various documents frequently mention the term Basic Automotive Chassis (BAC). This article uses the definition to include all MAF chassis (MPV, SWC, special tracked chassis, tractor chassis, trailer and semi-trailer chassis, etc) which are used as weapons platforms, transporters and towers, and combat support vehicles. Some 95 per cent of the Russian MoD’s mobile ground weaponry and military equipment is currently mounted on BACs; more than 1,500 models are in use1 (1,558 in 2005).2 In recent years, the proportion of weapons and military equipment mounted on BACs in the different armed services was as follows:

Army: 80 per cent

Air Force: 99 per cent

Navy: 98 per cent

Other services, including the Strategic Missile Troops: 97 per cent 3

Composition of the MAF

Back in Soviet times, specialists of the Main Automotive Directorate of the Soviet MoD4 (GLAVTU) calculated the following optimum values for the age of the MAF: 60 per cent should be under six years old; 30 per cent six to 12 years old; and 10 per cent older than 12 years.

In the 1960-1980s the Soviet Union implemented a set of fairly robust fleet refresh programs in an effort to stay close to those optimum values.

The situation took a sharp turn for the worse after the break-up of the Soviet Union. Financing of MAF procurement programs shrank by more than 90 per cent, and the fleet began to age very rapidly. The supply of spare parts also dried up. By 2005 the age structure of the MAF was a direct threat to the country’s defense capability. At least 80 per cent of the fleet was older than 12 years; vehicles between six and 12 years of age made up only 13 per cent of the MAF, and under six years 7 per cent.5

The bulk of the MAF consisted of decrepit and obsolete hardware which had long been discontinued by the manufacturers. To illustrate, in 2005 obsolete petrol-engine AWD models made by ZIL made up 33 per cent of the fleet.6 Most of the vehicles still in service were designed in the late 1960s or early 1970s. All of them were hopelessly outdated. Much of the fleet ran on petrol rather than diesel, and some of the Soviet manufacturers became foreign suppliers after the break-up of the Soviet Union – including KRAZ (6 per cent of the fleet), MAZ/MZKT, LuAZ, and several others.

Structure of the Russian MAF in 2005

Source: author’s data.

Owing to delays with the launch of new diesel engine models before 1991, as well as a sharp reduction in procurement programs after 1991, by 2005 diesel models made up only 29 per cent of the Russian MAF; the rest ran on petrol.7 Nevertheless, the structure of the fleet by type of vehicles remained close to optimum indicators, and the proportion of multi-purpose vehicles (MPV, the most numerous category) is currently 91.5 per cent.8 That is because the vast majority of mobile weapons systems use MPV chassis; in addition, multi-purpose transports make up the bulk of the military support fleet. Special wheeled chassis and wheeled towing vehicles make up 1.1 per cent of the fleet (4,500 units in total). The Russian Armed Forces are the only major armed service which treats such chassis and vehicles as a separate category. These vehicles are used as platforms for especially important weapons systems which can often decide the outcome of a battle. Military Tracked Vehicles (MTV) make up 7.4 per cent of the fleet (28,000 units in total). This category provides transport and mobility in difficult terrain, including territories in the far north, and provides support for the Army’s armored vehicles.

In recent years the age structure of the Russian MAF has begun to improve thanks to a general improvement in the economy, which has enabled the government to ramp up procurement programs. By April 2008 the proportion of vehicles older than 12 years had fallen by 5 percentage points. The overall situation, however, remains difficult.9 The MAF category with the greatest number of old and obsolete vehicles is MTV; the category of special wheeled chassis and towing trucks is not in a much better state. The fleet of general-purpose military vehicles is younger, but the situation here is also far from ideal.

The August 2008 war with Georgia highlighted the need for an urgent fleet refresh. By late 2012 the age structure of the fleet had shown a distinct improvement. Vehicles aged 12 years or more made up 57 per cent of the fleet; 6-12 years 14 per cent, and less than 6 years 29 per cent. But achieving an optimum age structure of the fleet will require a much greater effort.10 Although that structure has changed significantly over the past seven years, the proportion of vehicles working on diesel remains the same, according to Russian MoD sources. It is not exactly clear how that is possible, given that all the main suppliers, including Ural and KAMAZ, have mostly switched to diesel engines; indeed some don’t have any petrol engines at all in their model range. KAMAZ has supplied more than 30,000 AWD vehicles to the MoD since 2005,11 most of them working on diesel. Suppliers such as Ural and BAZ have not been selling any petrol models to the MoD for over 20 years. In all likelihood, the official MoD figures regarding the proportion of diesel engines are inaccurate. The present author believes that the actual figure is at least 36 per cent of the fleet. The MoD’s strategy for MAF development until 2020 includes a substantial increase in the proportion of modern engines in all vehicle categories. By 2015 vehicles equipped with diesel engines, as well as modern engines of other types, could make up 50 per cent of the fleet.

The overall size of the MAT stood at about 410,200 vehicles as of late 2012,12 more or less unchanged from 410,800 vehicles in 2005. The figure included 264,400 BAC vehicles, of which about 90 per cent were being used as weapons platforms, and 10 per cent as transports or towing vehicles.13

Soviet heritage

Most of the Soviet truck manufacturers offered mass-produced MAF models of their own design (with the exception of several plants which used existing designs developed elsewhere, the so-called “secondary” plants). In the 1980s, wheeled MAF vehicles were mass-produced by the following companies (the list is not complete):

Ulyanovskiy Auto Plant (UAZ)

Gorkovskiy Auto Plant (GAZ)

Moscow Likhachev Auto Plant (ZIL)

Urals Auto Plant (UralAZ)

Urals Auto Motors Plant (UAMZ)

Kamskoye Truck Production Company (KamAZ)

Kremenchug Auto Plant (AvtoKrAZ)

Bryanskiy Auto Plant (BAZ)

Special wheeled towing vehicles unit of the Minsk Auto Plant (PSKT MAZ)

Kurganskiy Wheeled Towing Vehicles Plant (KZKT)

Lutskiy Auto Plant (LuAZ)

Some of these plants also manufactured vehicles designed by other suppliers, serving as “secondary” plants. For example, UAMZ manufactured some models developed by ZIL. KZKT was set up to manufacture special-purpose vehicles designed by MAZ. In the mid-1980s the Orsk Tractor Trailer Plant was working on a project to take over the mass production of the SKSh 135LMP model developed by BAZ – but the project was put on hold after the launch of Perestroika. The strategy was used not only to increase production capacity, but also to keep in production some of the older models which were still in demand as weapons platforms. The transfer of mass production of such models to “secondary” plants enabled the primary supplier to launch new models without disrupting the supply of the previous one. Such an approach was used because there were a lot more weapons models than BAC models used as chassis and platforms for those weapons. Replacing all the older weapons models in one go was impractical – that required a lot of changes in the documentation, lengthy tests and trials, and possibly even changes in the design of the chassis and/or the weapon itself. Weapons designers were always reluctant to go to such lengths. It therefore made more sense to keep both the older and the newer vehicle designs in production, and then gradually to phase out the older model still in production at the “secondary” plants. Unfortunately, these older models often had to remain in production much longer than originally envisaged. For example, production of various modifications of the ZIL-157 vehicles for the Soviet/Russian MoD continued for 35 years, from 1958 until 1992.

There were several suppliers of MTVs in the Soviet Union in the 1980s; many of them were tractor plans operated by the defense-related ministries. The list included:

Mytishchinskiy Machinery Plant (MMZ)

Lipetskiy Tracked Towing Vehicles Plant (LZGT)

Kirovskiy Plant

Volgogradskiy Tractor Plant (VgTZ)

Zavolzhskiy Tracked Towing Vehicles Plant (ZZGT)

Muromskiy Locomotives Plant (Muromteplovoz)

Urals Railway Carriages Plant (Uralvagonzavod, UVZ)

Urals Transport Machinery Plant (Uraltransmash)

Ishimbayskiy Transport Machinery Plant (Ishimbaytransmash)

Rubtsovskiy Machinery Plant

Kurganmashzavod (KMZ)

Chelyabinskiy Tractor Plant (ChTZ)

Transport Machinery Plant

Minsk Tractor Plant (MTZ)

Malyshev Plant

Kharkiv Tractor Plant (KhTZ)

A total of 180 companies throughout the Soviet Union were involved in the production of MTVs.

Soviet MTV supplies, just like the makers of wheeled vehicles, preferred to mass-produce their own designs. But the tracked chassis and platforms for key weapons systems were completely standardized, and there were at least two suppliers for each model. For example, at least two different companies (and possibly more) produce the chassis used for the S-300V SAM systems. Nevertheless, the situation remained far from ideal. This is what V.A. Kukis, the chief designer at Uraltransmash, had to say on the matter: “I think there should be no more than three types of chassis: light, medium, and heavy. Actually, we have never had more than those three types. But previously, when there was a large number of different suppliers, there were three types but many subtypes - a lot more than was really required. The ambitions of those numerous suppliers led to a ridiculous situation whereby there were numerous different models within the same category.”14

As a result, the MAF inherited by Russia from the Soviet Union consisted of numerous types and models of vehicles (41 basic models and over 60 modifications).15 As a result, the level of standardization and interchangeability was clearly insufficient, making the whole fleet more expensive and difficult to run and maintain. The existing fleet also includes a lot of obsolete vehicles which have long been discontinued (including the GAZ-66, ZIL-157, ZIL-131, URAL-375, KRAZ-255, 135LMP, MAZ-537, and all the KZKT, GT-T, and GT-SM models).16

The Soviet and then Russian auto industry, including such suppliers as VAZ, UAZ, GAZ and ZIL, has developed and tested several new models specifically designed to cater to the MoD’s requirements (drawn up by GLAVTU/GABTU). In terms of their performance, these vehicles match or even surpass Western hardware. But for economic reasons, many of these new models have never entered mass production (including VAZ-2122, UAZ-3172, GAZ-3932, GAZ-3933, ZIL-4334, ZIL-4334.10, the BAZ Voshchina chassis, etc). Several other new models have been discontinued due to lack of defense procurement orders (the UAZ-3907, GAZ-3301, BAZ-5947, and the Susha family of standardized military vehicles, including Ural models 4322, 5323, 43222, 43224, 53234, 4422, and 44221-862).

After the break-up of the Soviet Union it turned out that some of the key MAF models were made only in Belarus or Ukraine, with no “secondary” suppliers in Russia. Great efforts had to be made to launch production of some of those models in Russia, or to develop indigenous Russian replacements. For example, MMZ has launched production of tracked chassis which were previously made in Minsk, and all the KrAZ models have been replaced by similar designs made by Ural, KAMAZ, and BAZ.

Notable exceptions include the MZKT-7917 and MZKT-79221 special wheeled chassis used in mobile ICBM systems such as Topol (SS-25), Topol-M (SS-27) and Yars (SS-29); these two models are still being imported from Belarus.

R&D problems

Up until 2009, procurement contracts for MAF vehicles were mainly placed by GABTU. Even in the 1990s, a very difficult period for the Russian Armed Forces, when government funding was severely reduced, The GABTU leadership did everything they could to preserve the physical assets and the expertise inherited from the Soviet Union. Development of new MAF models continued despite the crisis. Some of the R&D done during that period was used in the mid-2000s, when the economy picked up and the government was able to increase defense procurement spending. Several new models developed in the late 1990s and early 2000s have already entered service with the Russian Armed Forces, and large batches of these vehicles are being supplied to the troops.

But owing to lack of financing in the 1990s, several important MAF-related R&D projects were not completed. After the economy improved in the early 2000s, renewed efforts were made in that area. New projects included Yestestvennitsa (a new generation of automatic transmissions) and Ravnina (new tyres).17

After the appointment of Anatoliy Serdyukov as defense minister in February 2007, radical changes were made in the MoD’s approach to military research and development. In October 2008 the ministry suspended financing of all key MAF projects. But at the same time, industry began to implement a presidential decree which initiated the Platforma project.18 The goal was to develop a new generation of special wheeled chassis and towing vehicles using innovative technical solutions. The company chosen to implement the project was KAMAZ, which had no previous experience in that vehicle category. Two years later, in 2010, the MoD’s 21st Research Institute, which had long been the lead MAF research center, lost its independent status and became a branch of the MoD’s 3rd Central Research Institute.

As a result, supplies of MAF vehicles to the Russian MoD have been forced to resort to importing components from countries which are Russia’s potential adversaries. Imports also make the finished products more expensive, and launching indigenous production of such components has proved very problematic.

Suppliers and models of MPVs and SWCTVs

Below is a list of the main suppliers of vehicles in the MPV and SWCTV categories, as well as the main models being supplied to the Russian MoD:

KAMAZ (Mustang family of MPVs, Tornado family of heavy trucks, etc)

Ural (Motovoz-1 family of MPVs, Ural-6370 heavy trucks, etc)

AMZ (Tigr MPVs and their various modifications, chassis based on the BTR-80 APC design)

BAZ (Voshchina-1 family of SWCTVs)

MZKT (MZKT-543M, MZKT-7930, MZKT-79221 and other models of special wheeled chassis)

UAZ (UAZ-3151 MPVs and their various modifications, etc)

GAZ (GAZ-3308, GAZ-33097 Sadko and other MPVs)

The main Russian suppliers of AWD vehicles in the 14t to 40t category are Ural and KAMAZ. Their production capacity in the AWD segment is about the same; both also have a lot of spare capacity. The MoD would be very happy for the two producers to increase sales of their AWD vehicles to civilian customers because the fleet of such vehicles maintained in peacetime constitutes only about 40 per cent of the requirement in the event of a large military conflict. If a war breaks out with an adversary of equal or superior strength, the remaining 60 per cent will have to be borrowed from civilian operators. Over the past several years, MoD procurement of AWD vehicles has reached adequate levels – but the structure of the Russian MAF fleet remains far from ideal because in the preceding two decades supplies were well below the requirement. That is why MAF procurement programs need to be ramped up even further.

Ural and KAMAZ are currently mass-producing MPVs which entered into service with the Russian armed forces more than 10 years ago (Motovoz-1 and Mustang, respectively).

The Motovoz-1 family entered service with the Russian forces in 2002. It includes three basic models: two with conventional hooded cabins (Ural-43206, wheel configuration 4x4.1, and Ural-4320, 6x6.1) and one flat-nose model (Ural-5323, 8x8.1), capable of carrying 4t, 6t and 10t of cargo, respectively. The main advantage offered by the Motovoz-1 family is that they share about 85 per cent of parts and components. The initial plan for the four-axle truck was to use a KAMAZ cabin, but the idea was later abandoned. The choice was eventually made in favor of the IVECO EuroTrakker cabin. The Motovoz-1 family has several armored models. Another major advantage offered by these trucks is that they can accommodate a large variety of weapons systems which previously required several different models of chassis and platforms. That goes a long way towards resolving the fragmentation problems described earlier in this article, and helps to reduce costs.19

The Mustang family of MPVs entered into service with the Russian forces in 2002. It includes three standard models: KAMAZ-4350 (wheel configuration 4x4.1); KAMAZ-5350 (6x6.1), and KAMAZ-6350 (8x8.1), capable of carrying 4t, 6t and 10t of cargo, respectively. In 2003 the Mustang family underwent a radical modernization, and in 2004 KAMAZ launched five new models. Using the Mustang chassis, the company has developed the most comprehensive range of military MPVs in Russia and the CIS, with dozens of various modifications. Some of the modifications are armored, although they do not look any different from the standard models. The Mustang family has been chosen to form the core of the MoD’s fleet of new vehicles; the ministry has stopped buying obsolete models. It has also drawn up a list of approved models, which has recently been amended to include new Mustang modifications. At the same time, the older KAMAZ-43114 and KAMAZ-43118 models remain in production and are still being bought for use as weapons platforms by some weapons systems makers.

In recent years KAMAZ began to use some imported components in the Mustang family, including gearboxes and transfer boxes assembled in Naberezhnye Chelny by ZF-KAMA, a joint venture with Germany’s ZF. But the German company is intentionally trying to delay the localization program, and sending signals to the effect that it will never transfer the key underlying technologies to the Russian partner. Meanwhile, it has been reported that URAL is also considering the use of imported parts and components.

The Russian armed forces are currently buying AMN-233114 Tigr-M armored vehicles (wheel configuration 4x4.1) equipped with Russian-made YaMZ-5347-10 engines. When Tigr first went into production, those engines were not available, so all Tigr modifications were fitted with engines designed by the U.S. company Cummins and assembled in Brazil. These imported components were the reason why the Tigr entered into service with the Russian armed forces in 2007 with a proviso “only for units of the General Staff”.20 Now that a Russian-made engine has become available, reliable sources say that the AMN-233114 Tigr-M model will soon enter into service with the Russian forces without any provisos.

Information about the numbers of MAF vehicles supplied under the defense procurement program is not widely publicized. Nevertheless, some figures were announced on February 22, 2013 by Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin during a visit to AMZ. According to a presentation held during the visit, AMZ will make 146 Tigr units in 2013, including 65 to be supplied to domestic customers and 81 destined for exports. As of early 2013, the number of Tigr vehicles under the manufacturer’s warranty was 245.21 That probably includes not only the MoD fleet, but also vehicles supplied to other uniformed agencies, including the Interior Ministry. A certain number of Tigr vehicles has also been sold to civilian customers, meaning that this is now a dual-use model.

Following the liquidation of KZKT, BAZ is the only remaining Russian maker of mass-produced military vehicles in the SWCTV class. In 2003-2004 the Voshchina-1 family of SWCTVs made by BAZ entered into service with the Russian armed forces. The manufacturer launched their mass production, and began to supply them under the defense procurement program. Some of these vehicles are also being supplied to civilian customers because it was decided early in the R&D phase that Voshchina-1 would be dual-purpose technology.

The family currently includes the following models:

BAZ-6909 (basic model), a special wheeled chassis (SWC) with an 8x8.1 wheel configuration

BAZ-6910, an SWC with a larger cabin and an 8x8.1 wheel configuration

BAZ-6909.8, a special crane chassis, 8x8.1

BAZ-69092, an 6x6.1 SWC

BAZ-6306, an 8x8.1 ballast prime mover

BAZ-6402, a 6x6.1 trailer tractor

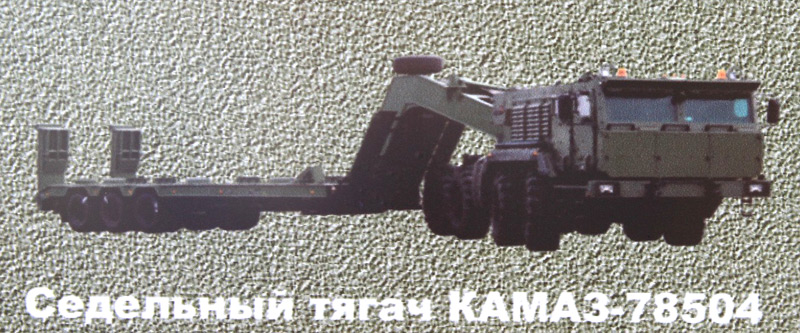

BAZ-6403, an 8x8.1 trailer tractor22

The main advantages offered by the Voshchina-1 family include:

Standard interchangeable parts and components

Independent torsion-bar suspension of all wheels, which increases the average speed, improves comfort in the cabin, and is easier on the roads and on the cargo being transported

Offset wheel-hub drives, which allow for greater road clearance and better off-road capability, even though the vehicles use smaller tyres than the AWD models designed by MZKT and KZKT

Several other advanced engineering solutions

BAZ has achieved a high degree of standardization and interchangeability by using a modular design. The main modules are the frame; the axle modules; the engine compartment, and the cabin. These modules can be assembled into various chassis configurations with a load-bearing capability of up to 45 tonnes. Such chassis can accommodate almost every single type of the existing and future weapons systems (with the exception of mobile ICBMs). The modules can also be assembled into ballast prime movers for heavy artillery systems or aircraft, as well as trailer tractors which can tow trailers weighing up to 70 tonnes. The Voshchina-1 family currently does not include five-axle or six-axle SWCs. BAZ says, however, that it can develop such chassis and launch their mass production very quickly if the MoD were to place an order for them.23 In 2011 the company made 87 Voshchina-1 vehicles; in 2012 output rose to 115 units. The figure includes civilian modifications and export versions of the SWCs.24

The SWC model currently being supplied for use as launchers for the Topol-M and Yars mobile ICBMs is the MZKT-79221 (16x16.1), with a carrying capacity of 80t. MZKT launched its mass production in 2005. In 2003 the MoD entered into service the MZKT-7930 SWC model (its mass production began back in 1998). There is also the MZKT-7930 (8x8.1), which can carry 22-25 tonnes, and is used as a platform for various existing and future weapons systems, including the Iskander-M (SS-26) tactical missile system; the Bastion (CSS-5) coastal defense missile system; the S-400 (SA-21) SAM system; the Uragan-1M MLR system; and several others.

Information about the numbers of MZKT chassis supplied to customers has never been made public. Judging from various news photos and reports by news agencies, as well as MoD press releases, it appears that the manufacturer continues to supply the MZKT-79221 and MZKT-7930 chassis for use as weapons platforms in the Strategic Missile Troops service (i.e. ICBM forces); and the MZKT-7930 chassis for weapons operated by the Army and the Air Defense service of the Russian Air Force.25 There have also been reports about deliveries of the obsolete MAZ-543M or MZKT-543M SWCs for use as launchers of the S-300P or S-400 SAM systems.26 Those reports, however, may not be accurate because the MAZ-543M chassis (if that was indeed the model supplied to weapons manufacturers) could have been existing stock from the storage bases. In addition, the MZKT-7930 SWC model was designed specifically to replace the 543 family, so it would be interesting to find out what the MoD, MZKT and the weapons manufacturers have to say about those reports. BAZ offers an indigenous Russian alternative to MZKT-7930 - namely, the BAZ-6909-013 model, which is actually superior to the Belarusian chassis in terms of its specifications.27

There is no precise information about deliveries of UAZ vehicles. The UAZ-3907 Yaguar amphibious model has been approved for use in the Russian armed forces, but the company has not managed to launch mass production. The same applies to the UAZ-3172, which was supposed to replace the obsolete UAZ-3151 model (a modernized UAZ-469).

UAZ is now part of the Sollers Group, and is very secretive about its MoD contracts and all related issues. But based on indirect evidence it is safe to assume that either the company has not even tried to develop any new models for defense customers over the past 20 years, or its efforts have not come to fruition. Any such models were bound to be dual-use products, and no such products have been demonstrated to the public. The most recent reports about MAF vehicles made by UAZ date back to 2003 and 2004.

In addition, UAZ has failed to find a Russian supplier of diesel engines and gearboxes for its vehicles. Its current ZMZ-514 diesels (ZMZ-5143.10, ZMZ-5148.10) are woefully inadequate even for civilian use, and do not meet the MoD’s specifications. In 2008, shortly before the global economic crisis broke out, ZMZ, which is also part of the Sollers Group, announced that it had begun to assemble Italian F1C diesel engines used in light trucks and off-road vehicles. But the company has not managed to launch mass production of that engine, so it later considered the option of importing various components for its vehicles, including diesel engines and gearboxes. For a number of reasons, vehicles using such components cannot be approved for use by the Russian armed forces.

The Zashchita corporation has developed several innovative protected vehicles of the Skorpion family using UAZ parts and components. The company initially targeted the export market, which is why it also used various imported components. The Russian MoD has shown interest in the Skorpion, but it has also expressed reservations about the use of imported components.

The role of GAZ as a MAF supplier is gradually diminishing. The company has failed to develop a successful model for the Airborne Assault Troops using the design of the Sadko truck as a starting point. Meanwhile, its competitor KAMAZ has developed the KAMAZ-43501 modification for use by the indicated armed service. The Sadko vehicles have been approved for use in the Russian armed forces, but orders have been very small so far (partly in an effort to reduce the number of various models operated by the MoD).

Conclusion

Many Russian manufacturers of MAF vehicles have lately been eager to incorporate imported components in their products, which makes the use of these products by the Russian armed forces problematic. Imports mean that the supply system is easier to disrupt, and on the whole, they make the MoD’s fleet maintenance system more vulnerable.

Many of the big Russian MPV makers have entered strategic partnership arrangements with the leading global supplies; for example, KAMAZ has partnered with Daimler AG. Others, such as Ural, are energetically looking for a strategic partner.31 These and other problems outlined above can have a serious impact on the development of the Russian military automotive fleet. That is why these problems require the attention of the Russian government and the president.

Although Russia is lagging behind its potential adversaries in some individual MAF categories, the overall level of capability in this area is roughly equal. Russian MAF technology has some clear advantages, including its level of readiness (a criterion which describes the availability of MAF vehicles in wartime), especially at below-zero temperatures. In addition, the off-road capability of Russian military vehicles is much superior to foreign competition.

1. http://www.minprom.gov.ru/appearance/report/73/print.

2. Russian Industry and Energy Ministry. On the implementation in the medium term (2005-2008) of priority programs under the Concept of Development of the Russian Auto Industry. Materials for the Russian Cabinet sitting of May 19, 2005.

3. Ibid.

4. On December 2, 2004 GBTU and GLAVTU became the Main Auto, Armor and Tank Directorate of the MoD (GABTU).

5. Privalov A. There will be only one victor // Gruzovik Press, 2013, No 2.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. http://www.oborona.ru/includes/periodics/authors/2011/0905/21217287/print.shtml.

10. Privalov A. There will be only one victor // Gruzovik Press, 2013, No 2.

11. http://twower.livejournal.com/1014295.html.

12. Privalov A. There will be only one victor // Gruzovik Press, 2013, No 2.

13. Using new-generation auto platforms for future weapons systems. Col. Oleg Morozov PhD, head of department at the 3rd Central Research Institute of the Russian MoD. November 15, 2012.

14. Zheltonozhenko O., Belogrud V. Pride of the Russian defense industry // Uralskiye voennye vesti, 2012, No 37-38.

15. Using new-generation auto platforms for future weapons systems. Col. Oleg Morozov, head of department at the 3rd Central Research Institute of the Russian MoD. November 15, 2012.

16. Russian Cabinet Resolution No 1091 of September 11, 1998 “On decommissioning (ending procurement of) MAF systems”.

17. Privalov A. There will be only one victor // Gruzovik Press, 2013, No 2.

18. Three to twelve. Department for research and testing of special wheeled chassis and towing vehicles is 50 years old (1959-2009) / Edited by P. Tarasov – Bronnitsy: 21 NIII IO RF, 2009, P. 72-73.

19. Fedechkin D. Standardization and interchangeability the new priority // Uralskiy Avtomobil, April 5, 2004.

20. Privalov A. New members of the Tigr family // Kommercheskiye avtomobili + spetsavtotekhnika, 2012, No 5-6.

21. http://bmpd.livejournal.com/466608.html.

22. http://www.autocatalogue.ru/html/news/2010/r0429000.htm.

23. Ibid.

24. http://autocatalogue.livejournal.com/60702.html.

25. Trends in the development of special wheeled chassis and wheeled military towing vehicles // Edited by V.A. Polonskiy – Bronnitsy: 21 NIII IO RF, 2007, P. 29, 192.

26. http://pressa-tof.livejournal.com/79094.html.

27. Privalov A. Born to crawl at the Air Force’s 100th anniversary celebrations // Gruzovik Press, 2012, No 11.

28. Privalov A. TVM-2012: No big announcements at the forum // Kommercheskiye avtomobili + spetsavtotekhnika, 2012, No 7-8.

29. Ibid.

30. Ibid.

31. URAL Auto Plant 2011 Annual Report.

Centre for Analysis of Strategies and Technologies (CAST)

Russia, Moscow, 125047, 3 Tverskaya-Yamskaya, 24, office 5

phone/fax: (+7-495) 775-0418. www.mdb.cast.ru