Fun article to read but you need (as always) to cut trough some very thick BS and standard talking points.

It's hilarious to watch the author try to claim that Russia is financial basket case while at the same time warning that Ukraine will go to the dogs due to Russia's expanding economic projects...

Last month, Russia completed a railway that bypasses Ukraine. The project was entrusted to a special military unit and completed a year ahead of schedule, underscoring its importance to the Kremlin. It is the latest of several Russian-led infrastructure projects that, coupled with the devastation wrought by the conflict with Russian-backed separatists in the Donbas region, risk turning Ukraine, historically a bridge between east and west, into an island.

Isolation from emerging east-west connectivity could be one of the most enduring and most damaging consequences of the war for Ukraine, one that both Kiev and its western partners need to pay more attention to overcoming.

Not long ago, Ukraine hoped to become a major gateway along China’s Belt and Road, a massive connectivity initiative stretching across Eurasia and beyond.

“The idea of the Great Silk Road will be actively supported by Ukraine,” then-President Viktor Yanukovich said during his visit to Beijing in 2013. Agreements promising $8bn in Chinese investment were signed, including a $3bn port in Crimea. But those deals were among the casualties of the armed conflict that erupted in early 2014.

So too were many existing connections between Ukraine and Russia, which were either damaged in the fighting or deliberately severed as a form of economic pressure.

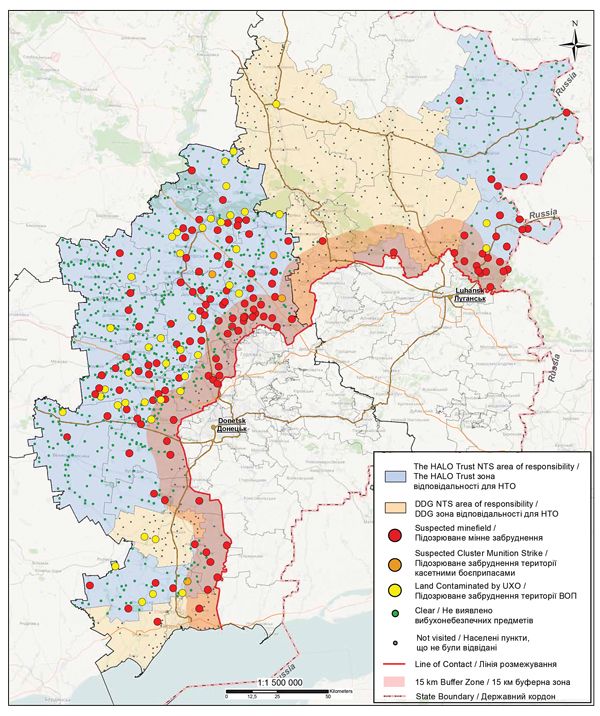

Ukraine’s conflict also disrupted internal connections between separatist-held regions of Donetsk and Lugansk oblasts and the rest of the country. In the early days of the fighting, separatist forces targeted critical infrastructure in eastern Ukraine.

A UN assessment in November 2014 found that 53 bridges, 45 road sections, and 190 railway facilities had been damaged. Altogether, infrastructure losses were estimated at $440m, and while some repairs have been carried out, funding constraints and security challenges have limited reconstruction.

The toll has been highest for people living in disputed territory, where neither Kiev nor Moscow is eager to assume the financial burden of governing. Near the contact line, once-routine movements are inefficient and even perilous. In the Lugansk oblast town of Stanytsia Luhanska, which was temporarily captured by pro-Russian separatists, elderly residents must struggle across a damaged bridge that separates territory controlled by rival forces. In government-controlled territory, protesters have blockaded railways, disrupting coal shipments and other trade.

For both sides in the conflict, altering patterns of trade and transit is a means of shaping Ukraine’s political and economic destiny. While military forces have destroyed critical infrastructure such as bridges and railways, the governments in both Kiev and Moscow are building new connections that will re-orientate trade flows.

When Russian-backed separatists seized Crimea in early 2014, Ukraine cut off road and rail links to the peninsula, along with water supplies, banking, and other services. In the autumn of 2015, Crimean Tatar activists blew up electricity pylons, temporarily halting the flow of electricity from the mainland to Crimea. These steps have reinforced Crimea’s isolation from mainland Ukraine, worsened poverty on the peninsula, and imposed significant costs on the occupying Russians.

As Kiev has sought to isolate Crimea economically, Moscow is building new linkages designed to further integrate Crimea with Russia. Leading the list is a $4bn bridge that Russia is building across the Kerch Strait to Crimea, accompanied by a $2bn highway. The bridge has become a pet project for Russian President Vladimir Putin, who tasked a member of his inner circle with constructing it and has called the effort a “historic mission”. Intended to open at the end of 2018, it has numerous hurdles to overcome: sanctions, harsh weather, unruly soil and even seismic activity.

Also shaky is the economic case for the bridge. It is designed to carry an estimated 13m tons of cargo and 14m people between Russia and Crimea each year. In practical terms, that means the bridge could accommodate all the tourists that visited Crimea last year by ferry, plus annual round trips by every man, woman and child living in Crimea. Expanding the ferry service would be more cost-effective, but that would undercut the project’s main objectives: transferring public wealth into favoured private hands and showcasing Russia’s power.

While Russia builds into Crimea, it is building around Ukraine in other ways. The recently completed railway bypass cuts off a 26km stretch of Ukrainian railway, freeing Russian shipments to Belarus, the Baltics, and other points south from having to cross Ukrainian territory. Traffic along the route could grow after the long-awaited North-South Transportation Corridor, which stretches from Moscow to Mumbai, becomes operational. If Ukraine remains cut off, it will miss out on this growth.

Russia is also building pipelines that will decrease its reliance on Ukraine, which now touches nearly half of Russia’s gas exports to Europe. Nord Stream 2 would double the capacity of an existing route between Russia and Germany. Targeted in a recent US Senate sanctions bill, the project has been embraced by five European states and opposed by others in central and eastern Europe. Despite opposition, it aims to start delivering gas in 2019.

A related project, Turkish Stream, envisions two undersea pipelines connecting Russia and Turkey across the Black Sea. The first pipeline will primarily serve the Turkish market, while the second will serve southern Europe. Construction of the first pipeline began in May and is scheduled to become operational in 2019. Connecting to the EU will require overcoming regulatory hurdles, which require unbundling infrastructure ownership from transmission, as well as the opposition of the European Commission.

Completion of Nord Stream-2 and Turkish Stream would allow Russia to continue servicing European customers while dramatically reducing the volumes of gas it ships through Ukraine. Not only would Ukraine lose out on transit fees, it would face the possibility of Moscow cutting its gas supplies off in a crisis. In previous crises, if Russia cut gas supplies to Ukraine, it risked leaving its European customers without gas as well, encouraging the Europeans to push hard for a resumption of supplies. If the two bypass pipelines are completed, European and Ukrainian interests will diverge to a much greater degree.

None of these infrastructure projects are game-changing on their own, but taken together, they preview a Ukrainian state that is increasingly isolated from its traditional trading patterns. This connectivity challenge is multidimensional, extending beyond bilateral relations with Russia and beyond hard infrastructure. The Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union, for example, includes Belarus and, by imposing new customs barriers, limits Ukraine’s possibilities for trade with its East Slavic neighbours. Ukraine’s losses could mount as new routes emerge and the Eurasian supercontinent connects without it.

Russia’s efforts to isolate Ukraine economically make it imperative for Kiev to deepen trade and transit ties to the west. Some Ukrainian trade has already shifted from Russia to the EU, which received 37 per cent of Ukraine’s exports in 2016, up from 25 per cent in 2012. That figure should continue to rise following the ratification of the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement by the European Commission in July 2017. Yet even as the volume of Ukraine’s exports to the EU increased, they also declined in value. The shift has also favoured exports of agricultural products, while manufactured goods have suffered, since few of Ukraine’s industries are competitive inside the EU.

To cope with reduced connectivity to its east, Ukraine and its European partners need to reinforce their efforts to promote connectivity to the west.

Infrastructure upgrades would help. Ukraine has one of the largest railway networks in Europe, but its rolling stock is ageing and needs to be replaced. Ukraine’s ratio of highways to land, lags far behind its European peers, and most roads do not meet international standards. Ports handle the bulk of Ukraine’s international trade and with grain exports at record levels, they could benefit from improved grain handling capacities. Factories must also be upgraded so that more products meet EU standards.

All of this will require investment, which means that Ukraine must get its own house in order. Kiev has moved too slowly on reforms to reduce corruption, promote foreign investment (allowing foreign land ownership, for example), and privatise state-owned enterprises.

As Russia’s infrastructure projects underscore, the world is not sitting still. Ukraine’s western window will not remain open forever.